CONSULTATION PREMISE #2: In the New Future of ecological trauma, a faith that primarily accentuates widely-held positives—the comforting assurances upon which optimistic religion depends—will become increasingly unintelligible to those seeking wholeness and hope in this world. It is not unfaithful to admit this.

By John Elwood

Last autumn, the “Faith Factor in Climate Change” report showed up in my in-box. I had been waiting anxiously for this: PRRI’s ten-year update analyzing how religion impacts American attitudes on environmental policy. Surely, our efforts at “creation care” advocacy would have yielded some progress, I told myself.

I already knew much of what I would find: that secular Americans would hold the most constructive attitudes toward climate policies, and that Christians—most of all, White Evangelicals—would lead the way in denial and inaction. But surely there would be progress, I hoped. At first glance, the report did not surprise. Page after page told the story every Christian environmental practitioner knows by heart. Is climate change actually happening? Is it tied to human activities such as fossil fuels? Will God intervene to prevent human ecosystem destruction? As expected, in each case the attitudes of self-identified Christians would tend toward apathy and inaction, more than any other religious demographic.

But deep in the report, I came across the real shocker: Already the least concerned about climate change ten years earlier, the percentage of White Evangelicals who considered climate change to be “a crisis” had actually fallen dramatically—from 13 percent to a mere 8 percent.[i] All the work of so many “creation care” advocates, it seemed, had amounted to almost nothing. White Evangelicals—our dominant religious tribe—were slipping backward, heedless of our best efforts and nature’s powerful voice.

What could possibly have gone so wrong? There would be no shortage of answers. Some of us focused on our strategies: we’ve neglected the best communications practices; we haven’t been sending out trusted messengers; we’ve been neglecting New Testament passages in our arguments; we failed to offer solutions palatable to free-market conservatives. Other answers looked toward our religious tribe itself: they’re Republicans, after all; the creationism wars have bred skepticism; they don’t properly understand their own religion; they’re free-market capitalists, and headed to heaven anyway—whatever happens to this world.

But a few had begun to wonder: What if these Christians were really acting consistent with their theology? With actual Christian theology, that is. What if they’re not stupid or disobedient? What if they’re just 21st century Western Christians? Like us?

The Two “Christs” of Christendom

Despite the claims of some guardians of orthodoxy, Christian theology is not static, like a frozen waterfall. In every age, Christ-followers have had to ask themselves Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s question from inside his Nazi prison cell: “Who is Christ, actually, for us today?”[ii] Bonhoeffer knew that Christianity not only shaped its context; it was also shaped by it—having arisen within a community devastated by brutal empires; amassing power and wealth as the palace priesthood of Constantinian Rome; spreading across the globe as the established religion of European colonialism; and lending spiritual credibility to the global hegemony of the American century. Bonhoeffer’s context—the prisoner of a state dedicated to unprecedented mass murder—was something, at least in its scale, entirely new. Who, actually, was Christ in such a world?

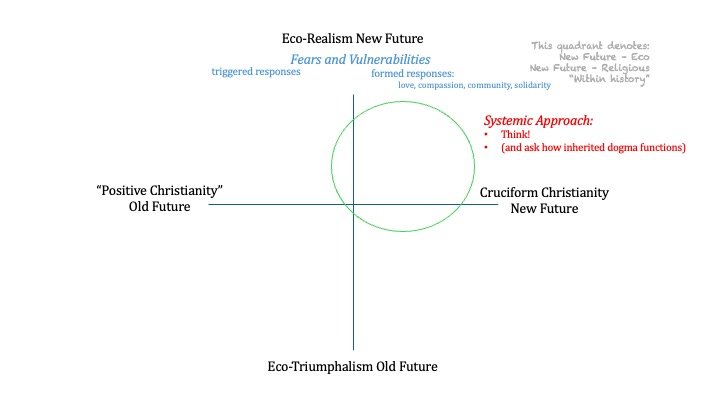

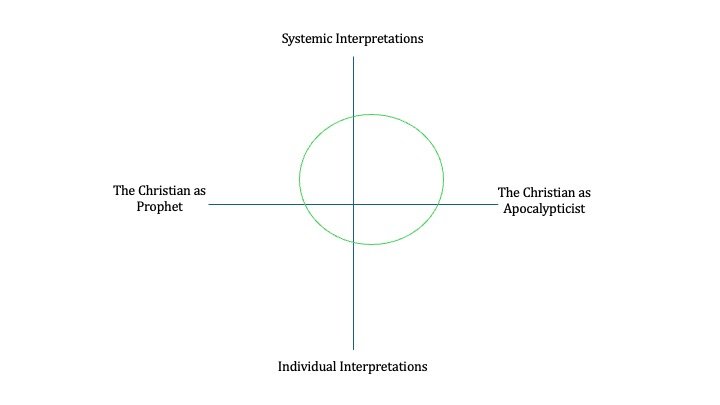

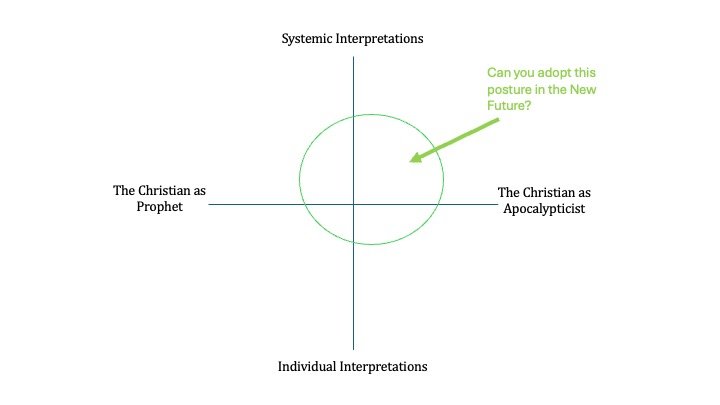

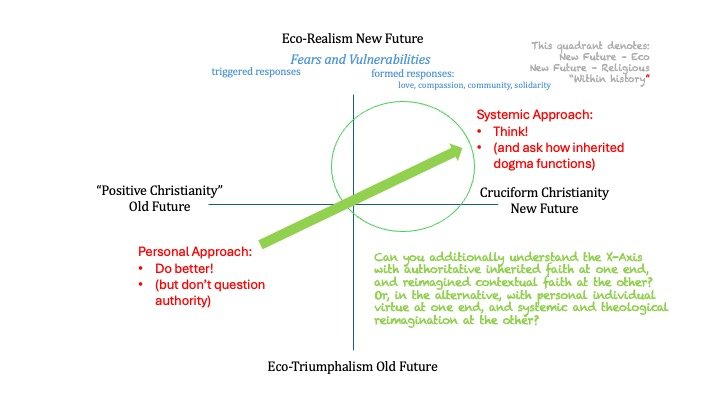

Last month, Lowell Bliss proposed what we are calling Premise #1: That we are facing a “new future” of “excruciating collapses, catastrophes, and/or extinctions for which our faith in current efforts at activism, sustainability, and/or technological innovation is unfounded.” He asked us to reconsider our environmental optimism—what he called eco-triumphalism—and to look at the future with unblinking eyes—what we are calling eco-realism. In these paragraphs, I will ask us to undertake a similar imaginative process in the realm of our theologies: Facing the “new future” wrought by ecosystem collapse, who, actually, is Christ for us today? What reimagination does this context demand of us now?

Broad-brush statements about any theology are often easy to dismiss, and difficult to defend. But I will dare to offer one here: There have been two major interpretive lenses in the history of the gospel, lenses that go by different names in different times and contexts. One of these we might call Positive Christianity—a theological frame that foregrounds themes of victory, certitude, and expectation of happy endings. Who is this Christ for us, we ask? Christ is the Sovereign Lord of all; the King of glory; at the right hand of the Father; if once the Lamb of God, now the Lion of Judah; if once suffering on the cross, now risen in power. The cross was an event in the history of this Christ, an event that is behind him now. Theologically, this Christ is experienced as “Christus victor” in our doctrines, liturgies, hearts and expectations.

The alternative frame we might call Cruciform Christianity, which foregrounds God’s solidarity and immanence amidst our suffering. Who is this Christ for us, we ask? This is divinity in the weakness and failure of the human condition; the One who does not open his mouth to his accusers; the brother of the least of his creatures; taking on the flesh of the most wretched of the earth. This is Emmanuel—God with us in our suffering; the broken Christ. This is Christ crucified, who suffers both for and with his loved ones. The cross—never an ephemeral event—reveals the eternal compassion of this Christ. In theological terms, this Christ is experienced as “Christus dolor” or the fellow-suffering Christ.

I will argue that while Christians often affirm both of these frames, the Church tends to foreground one—largely to the exclusion of the other; that it has never been a fair fight between the two; and that in the North Atlantic world, Positive Christianity has emerged as the unquestioned victor over Cruciform Christianity in whatever struggle there might once have been. Today, however, this Positive Christianity is becoming contextually unintelligible, and risks becoming toxic in the “new future”—a future which seems to contradict much of what centuries of official Christianity has taught us to anticipate.

Christus Victor and Religious Triumphalism

What I am calling Positive Christianity goes by many names. The Canadian theologian Douglas John Hall frames it in terms proposed by Martin Luther: the “theology of glory,” set against the “theology of the cross.” But recognizing the ambiguity of those terms to the contemporary mind, Hall proposes a more familiar term: Triumphalism. He writes:

“Triumphalism refers to the tendency in all strongly-held worldviews, whether religious or secular, to present themselves as full and complete accounts of reality, leaving little if any room for debate or difference of opinion and expecting of their adherents unflinching belief and loyalty. Such a tendency is triumphalistic in the sense that it triumphs—at least in its own self-estimate—over all ignorance, uncertainty, doubt, and incompleteness, as well, of course, as over every other point of view.”[iii]

In a word, Hall’s triumphal Christianity might simply be embraced as “the Truth,” leading its adherents to expect one thing above all: personal and cosmic triumph. Churches and individuals, in possession of this “complete account of reality,” which is promised to triumph “over every other point of view,” will always find it extraordinarily difficult to nurture solidarity, modesty, self-criticism, and genuine curiosity—the stuff of Cruciform Christianity.

Of course, it is easier to recognize triumphalism in others than in ourselves. For example, in the late 19th century, wherever American Christians looked, their culture, nation and religion were on the march. The pace of progress and Christian expansion was stunning. In churches popping up across the continent, ministers and their flocks were reading the religious bestseller of the era: Rev. Josiah Strong’s “Our Country.”

Strong’s book offers a snapshot of religious triumphalism on steroids, and its popularity revealed much about the culture of Euro-American Christendom. God had allied himself with Anglo-Saxon Christians, provisioned them with unfathomable resources and wealth, endowed them with the genius of industrial technology, and breathed into them a uniquely life-giving faith. The end result was practically inevitable:

“This race, of unequalled energy, with all the majesty of numbers and the might of wealth behind it—representative, let us hope, of the largest liberty, the purest Christianity, the highest civilization—having developed peculiarly aggressive traits calculated to impress its institutions upon mankind, will spread itself across all the earth.”[iv]

The order of the day was Manifest Destiny and an explosion of worldwide missionary zeal. Right around the bend was the dawn of the glorious American Century. Confidence and triumph were in the air. But, we ask, haven’t we moved on from all that? That pushy, domineering caricature so easily dismissed as something we’ve seen, but never embraced ourselves? Hall, however, won’t let us off so easily. In our own time, he observes:

“The church … would be the doorway—the only doorway, most Christians believed—to eternity. Thus, it would not only endure … but it would prosper! Other institutions—kingdoms, political systems, governments—might come and go; even divinely ordained offices and social structures could pass away, their usefulness ended; but as the portal of God's own kingdom, the church could expect a glorious future.”[v]

The Perils of Triumphal Christianity

Christianity has no monopoly on triumphalism. But if Hall is correct, assumptions and expectations near to the heart of Positive Christianity rest on this triumphal version of the faith: Christus victor leading us to global triumph or heavenly escape. But why would we argue that this particular religious frame is unsuited for the new future that we now face? For starters, the comforting expectations of a happy future have completely lost touch with the current and foreseeable experience of most of humanity and other forms of earthly life. Those who are most keenly aware of the suffering now locked in to a world of ecosystem failure cannot make sense of what religious people are talking about when they speak of a glorious future, unless that future is relocated outside of history.

Secondly, Positive Christianity must now pretend that we are still living in a world that has vanished over the last century. Despite the comparative growth in the churches of the Global South, our faith, once the culturally-established religion of the ascendant West, has experienced steep decline, both in numbers and moral standing.[vi] In 1940, 89% of Americans claimed to be Christians, and only 6% had no religious affiliation.[vii] By 2021, however, American Christianity’s share had declined to 63%, and the religious “nones” had more than quadrupled to 29%. And while three-quarters of Baby Boomers still identify as Christians, less than half of Millennials do, and only 22% of them regularly attend religious services.[viii] The graying remnants of a heavily Christian Western culture are giving way to more pluralist generations, one funeral at a time. We no longer live in a world of actual triumphant Christianity.

Thirdly, triumphalist religion tends to suppress this-worldly solidarity. God won’t let the most terrible things happen; if God does, it will happen to others, not us; and if it happens to us, we’ve already gained a spot in everlasting paradise. This faith-borne resistance to complete belonging and solidarity with the suffering world of our experience may well explain why survey after survey demonstrates that American Christians, and most notably White Evangelicals, care the least about looming ecological crises and social inequities.[ix] In the eyes of a world of suffering, it may appear that cross has become symbolic—not of fellow-suffering solidarity, but of abandonment and exclusive escape from hardship.

Finally, when positive religious expectations finally lose touch with the reality of our actual experience in this life and this world, religions tend to pivot toward focus on secondary worlds—including worlds of idealism or illusion. “The pain of this world is answered,” writes Hall, “by the creation of another, better world, where hope is possible and realizable.”[x] This world—the world of suffering and hopelessness that religion seeks to address—is bypassed in a last-ditch effort to offer some kind of hope. Hall writes:

“Consequently, religion becomes unbelievable to the most sensitive, honest, and earthbound…. The danger of such a religion, however, is not merely that those most committed to earth are excluded almost a priori, but that it carries off from the daily concern for earth many who might otherwise serve the causes of humanity more usefully.”[xi]